Imagine survival in an environment of extremes: during the daytime, which is 14 Earth days long, temperatures climb to 127°C (260°F) while the relentless sun beats down with no cover. When night finally arrives, for an equally long interval, temperatures fall to -173°C (-280°F). The landscape is incredibly rugged, filled with impact craters and covered in a fine dust so sharp it resembles tiny shards of glass. Direct contact with Earth is impossible. Instead, all communication is relayed via an orbiting satellite. This is the environment on the far side of the Moon, where the Lunar Surface Electromagnetic Experiment (LuSEE-Night) – a radio telescope set to deploy there in 2026 – will attempt to reveal new information about the Dark Ages of the Universe.

These Dark Ages took place about 380 – 400 million years after the Big Bang. LuSEE-Night provides an opportunity to listen to radio signals from this time in the Universe’s history – one that is only observable from this distant vantage. On Earth, this signal is absorbed and refracted by our atmosphere and lost in the overwhelming noise of human-produced radio and communications signals. A snapshot of this important and little-understood era in our cosmological history could help us better understand how our universe evolved over time.

“During the majority of the Dark Ages, no stars or galaxies had formed yet,” clarifies Kaja Rotermund, a postdoctoral researcher in Berkeley Lab’s Physics Division. “One advantage of observing this earlier time is that the physics governing the expansion of the universe should be simpler because we don’t have stars and galaxies complicating things.”

The far side of the Moon provides an ideal, radio-quiet environment for observing Dark Age signals, but it is not trivial to mount an experiment there. In fact, the first soft landing on the far side of the moon was only accomplished in 2019 by CNSA’s Chang’e 4 mission. When LuSEE-Night makes its journey to this remote destination, it will be one of only a few missions to land there. The experiment will be a trailblazer, with the intention of gathering data and demonstrating the effectiveness of equipment and radio antennas in the harsh lunar landscape.

Meet LuSEE

LuSEE-Night is made up of four Stacer antennas, each 3 meters in length, which will be tightly coiled during the journey and then spring open once deployed on the Moon. The antennas sit on top of a carousel that will allow them to rotate and change orientation. Below the antennas, the instrument will contain sensitive equipment, including a spectrometer and a battery, encased within a protective thermal enclosure. The whole system will be mounted on top of a Blue Ghost 2 lander.

After the lander touches down, it will permanently power off, thereby eliminating the potential for electronic interference with LuSEE’s sensitive radio telescope, and operations will then be dictated by the lunar schedule. During the day, it will charge its battery and communicate with Earth. Scientific observations will be made during both the day and nighttime periods.

The project is a collaboration between NASA and the DOE, with Brookhaven National Lab serving as the lead on the project and the UC Berkeley Space Sciences Lab, the University of Minnesota, and Lawrence Berkeley National Lab all acting as partners.

Berkeley Lab is responsible for building LuSEE’s antennas as well as the turntable the antennas sit on. Rotermund and Aritoki Suzuki, a staff scientist in the Physics Division who leads the LuSEE-Night project for Berkeley Lab, worked on the antennas for the project.

Suzuki has experience building antennas for other cosmic microwave background (CMB) experiments, though he is used to dealing with frequencies of around 100 gigahertz, where the wavelengths are in the millimeters. For LuSEE-Night, Suzuki is working with frequencies of around 10 megahertz, so the wavelengths are a thousand times longer than those he is used to dealing with for CMB experiments.

“Testing something that is a meter in size versus something that is a millimeter is completely different,” says Suzuki. “With a millimeter, I can design everything on the table. Everything is controlled. Whereas when we tested the meter-scale antenna, we went to this field in Northern California called Hat Creek, which is a radio-quiet site. Whatever they have is what I have to deal with: if there is a tree, I cannot cut down the tree, I have to deal with the tree. It was a lot less controlled.”

Engineering for extremes

Suzuki and Rotermund collaborated with Berkeley Lab mechanical engineer Joe Silber to create the carousel, a small but important component of the overall system. LuSEE-Night’s antenna array is not perfectly symmetrical – that’s why it’s been designed to sit on a carousel, which allows the antennas to rotate. By changing the position of the antennas, scientists can determine if their observations are cosmologically important or an artifact of the instrument’s asymmetry.

“The carousel is not a complicated machine in the conceptual sense,” explains Silber. “Where it gets interesting is in all the details to feel one hundred percent certain that it will work when it lands on the far side of the Moon and no one can touch it.”

Conceptual work on the carousel began with a number of requirements. The device needed to include a motor, an encoder to translate power from the battery into motion, a shaft to drive the motion of the carousel, a turntable for the antennas to sit on, a launch lock to keep all of the components from moving around during launch and flight, communication antenna support, and cable management. The carousel needed to be accurate enough to position the antenna array to within < 1° of accuracy. The device also needed to thermally isolate its sensitive equipment from the external environment. Moving components like the bearing needed to be sealed to protect it from lunar dust entering the system. All parts of the system needed to have a reliable ground to prevent static from interfering with scientific measurements. And finally, the delicate components of the carousel needed to be able to survive launch, spaceflight, and then be able to operate in the lunar environment for more than a year.

To ensure the carousel will function once it completes its journey to the Moon, Silber researched the different environments and conditions it would need to survive during its lifespan – from the humidity of the launch pad in Florida to the vacuum of space and its operational life on the moon.

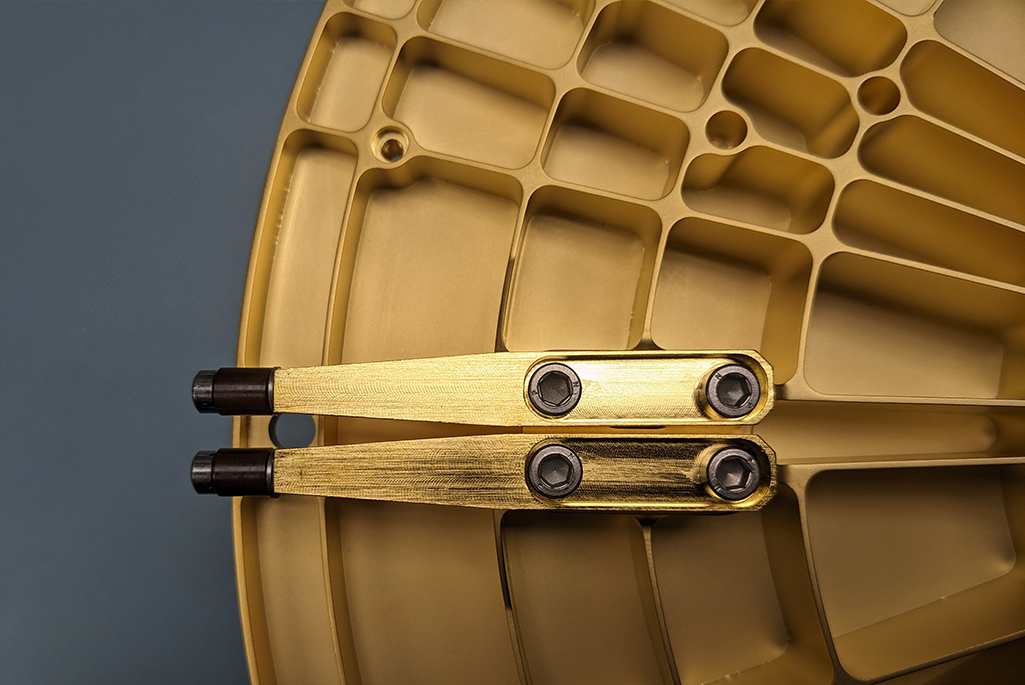

Detailed view of the pin lock assembly on the underside of the carousel. During launch and transit, the lock pin stabilizes the platter and prevents it from rotating. After landing, the pin is retracted, freeing the carousel to rotate. (Credit: Joe Silber, Berkeley Lab)

“One of the hardest things on the Moon is the thermal environment,” comments Silber. “It’s really one of the more challenging thermal environments you can design for. For a lot of the stuff we design for, we build it at room temperature and then we take it down super cold, or we build it at room temperature and then we get it super hot, but the moon is a different type of environment. So, at the depths of lunar midnight, you are going down to temperatures that are close to liquid nitrogen for days at a time. Then, during the lunar day, you are going up to temperatures that are well above boiling water. So, you have to design in both directions, and it’s just not that conventional to do that.”

LuSEE’s sensitive electronic components, including its battery, are all housed in a thermal enclosure to protect them from the harsh environment and keep them at consistent and relatively human-friendly temperatures. In order to bring data from the antennas to the sensitive instruments housed in the thermal enclosure, Silber had to figure out how to penetrate the casing without leaking heat.

“It’s not just that we penetrate the thermal enclosure with a cable,” Silber remarks. “It’s this rotating mechanical shaft with lots of cables inside it that all have to have special shielding for the instrument. We’re taking this signal from the antennas on the outside and bringing that signal into the enclosure where the sensitive instruments are. So, all of that has to penetrate without there being a significant thermal leak.”

To solve this problem, Silber explored several different routes, including putting the carousel’s motor outside the thermal enclosure. However, this would mean finding a motor that could endure lunar extremes. Ultimately, this idea was rejected, and instead the decision was made to house the motor within the thermal casing. While this protects the motor, it meant designing a thermally isolated spinning shaft that would connect the carousel to the motor.

Another detail of the carousel that a lot of thought went into was the bearing that would be used to rotate the device.

“One of the things we mechanical engineers enjoy doing is picking bearings, because there is a bunch of subtlety and technical art to it,” Silber says.

The central bearing assembly, which supports the carousel assembly. It contains a stiff, preloaded, crossed-roller bearing to prevent rattling during launch. The bearing is retained by flexural clips to allow for thermal expansion and contraction during the extreme temperature swings on the Moon. (Credit: Joe Silber, Berkeley Lab)

The bearings used in the carousel need to withstand intense acceleration loads and vibrations during launch. They need to be relatively stiff, so the carousel plate doesn’t move around or have a resonant vibration mode. The aluminum carousel is subjected to the heat extremes of lunar day and night, so thermal expansion of the plate versus the bearing was an important consideration to ensure that it will not bind and stick. Even the lubricant used for the bearing needed to be carefully selected to ensure that it would function in extreme cold.

Vacuum compatibility was an additional consideration. Many polymers, greases, and oils evaporate over time, which can cause issues with space-based optical instruments because they can coat optical detectors. While LuSEE itself is not an optical detector, the spacecraft relies on star cameras for navigation.

“I look at all the engineering that went into this, and I’m just blown away,” Suzuki remarks. “The vibration analysis, the thermal calculations, surviving the launch, stress analysis, picking the right materials, picking the right motor. I’m an instrument scientist. Can I make a turntable? Yes, I can. But it’s like me making a toy car versus making an F1 car. It really taught me the value of having an engineer who is trained to be an engineer.”

For engineers and scientists alike at the Lab, this is an unusual project because it involves a relatively small number of collaborators and has a quick turnaround time. The engineering design for the carousel was completed in under a year and went straight to prototyping. LuSEE-Night is currently scheduled to depart for the far side of the Moon in 2026.

“I’ve never worked on a project that is going to space before,” Silber remarks. “I’ve always wanted to design for space. It’s so cool – it’s a Moon radio!”