Video transcript from From Lab to Lifeworld: A practical methodology for responsible science and innovation (YouTube, 1:02:45), a talk presented by Ben Zevenbergen at Berkeley Lab on September 30, 2025. Learn more in this accompanying PSA News article.

_________

Natalie Roe: Good morning, everyone, and welcome. We’re delighted today to welcome Ben Zevenbergen. I actually met Ben at a conference last winter, and he gave such a great talk, so we invited him to come here and share what he does with us. Ben is an advisor and a researcher covering the philosophy and ethics of technology development. Most recently, he was a Responsible Innovation, Ethics, and Policy Advisor at Google. Before that – he has really an amazing resume – he completed a postdoc at Princeton in philosophy and computer science, he earned a PhD at Oxford, he worked in tech policy in the European Parliament, and he practiced as a tech law attorney in Amsterdam. So he’s had really a remarkable career, and he’s particularly passionate about interdisciplinary collaboration across academia, industry, government, and policy, exploring how technology can be designed and implemented responsibly in society, and Ben is currently launching his own venture. So, please, join me in welcoming Ben.

Natalie Roe: Good morning, everyone, and welcome. We’re delighted today to welcome Ben Zevenbergen. I actually met Ben at a conference last winter, and he gave such a great talk, so we invited him to come here and share what he does with us. Ben is an advisor and a researcher covering the philosophy and ethics of technology development. Most recently, he was a Responsible Innovation, Ethics, and Policy Advisor at Google. Before that – he has really an amazing resume – he completed a postdoc at Princeton in philosophy and computer science, he earned a PhD at Oxford, he worked in tech policy in the European Parliament, and he practiced as a tech law attorney in Amsterdam. So he’s had really a remarkable career, and he’s particularly passionate about interdisciplinary collaboration across academia, industry, government, and policy, exploring how technology can be designed and implemented responsibly in society, and Ben is currently launching his own venture. So, please, join me in welcoming Ben.

Ben Zevenbergen: Thank you so much, Natalie. And yeah, it’s so great to be here, I’m super excited, I’ve been looking forward to this for weeks now.

So, just a couple of things that I want to say today. I’ll go into a lot more detail, but I want to start off by saying that in the work that I’ve done, I’ve always advocated for technology and science to never be neutral artifacts. they’re always value-laden. And when you design things, you are also designing humanity at the same time. And then, you know, for technologists or for scientists, that means that the choices you make in your work, they’re actually ethical in nature, because you can go this way, or you can go another way, and the effects would be profound, or could be profound.

So then the question is, you know, if you do choose to accept that, then what do you do?

And that was kind of my challenge at Google. I’ll talk a little bit about that in a second, but first just to add to the bios, I used to actually be a musician. I started playing the drums at high school, went to the conservatory afterwards, worked at a record company. And at the record company, I noticed that they had no conception of the internet and what it was going to do to music, and they wanted to sell CDs and not join that innovation.

So I thought, if these are the people who are going to be in charge of my career, I better be a lawyer and actually start helping these startups that are going to be doing useful things, rather than, you know, being part of this aged structure.

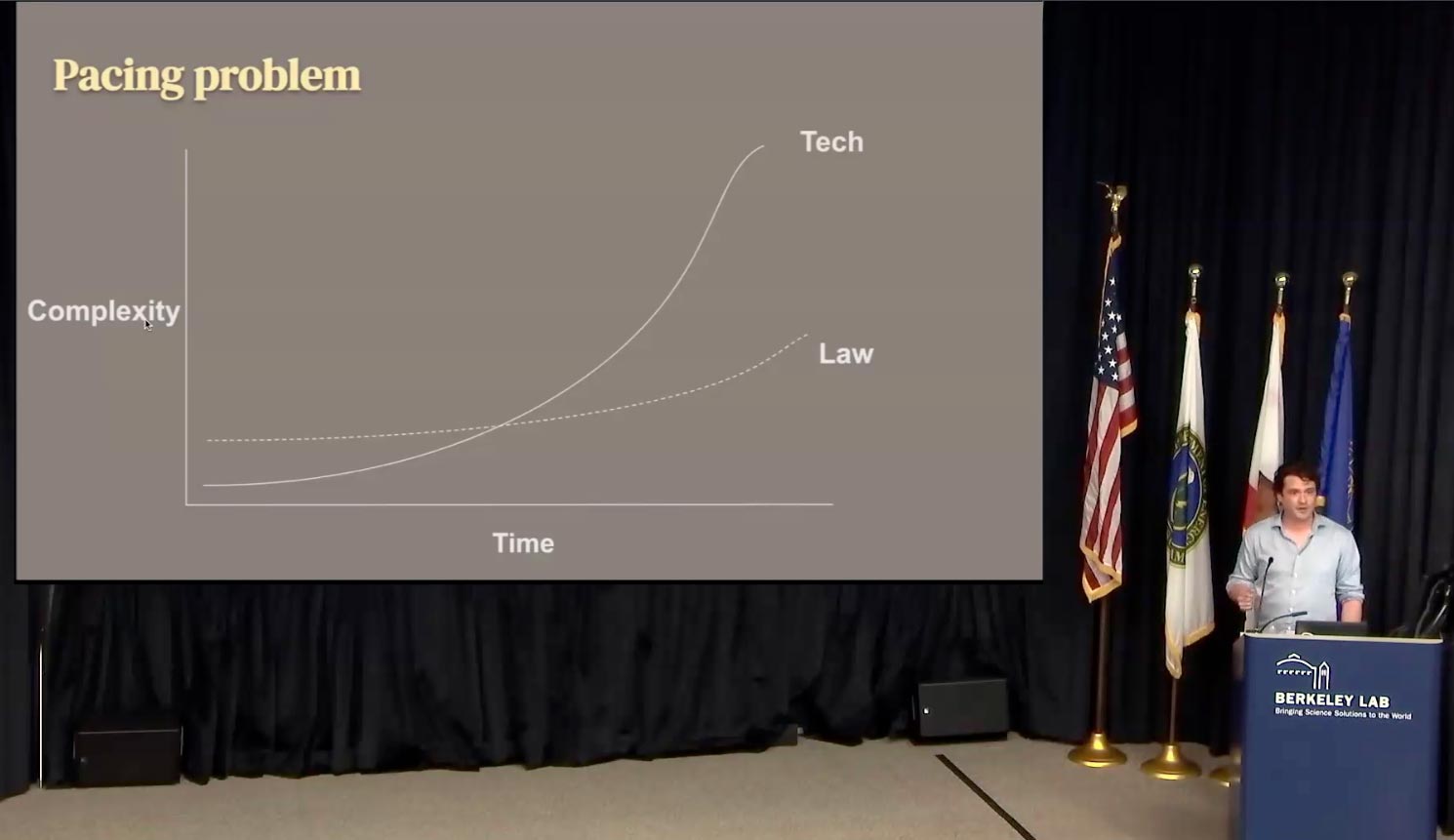

So I became a lawyer, went back to the Netherlands to study. I became a tech lawyer. For many anecdotes, I can tell about that time, but it was… I felt it was really hard to be a technology lawyer. Most of the time, I felt that my work was trying to – this is over in Europe, I’m sure it’s different here with the common law system – but, you know, we had laws written in a prior technological era. Those words described that era in some way. We’d moved on. You know, my clients would be innovative companies trying to do new things, so we would argue about, you know, can we stretch the meaning of the particular words to the current situation. And then the other party would argue the opposite, so it was basically semantics, and we weren’t actually getting to furthering the technology law. Sometimes it would happen, but it was just… I thought it was frustrating.

So I went to policy to help write those laws. And we spent a great time in the European Parliament, working with the European Commission, and also with Congress, to think deeply about, you know… how should we regulate this?

But an issue I found there was that if you find an issue to regulate, or you take an old law and you want to improve it, it’ll take about 4 years for it to actually be enacted, and then maybe another 2 years, after that, you know, you get a notice period or something like that, typically.

So, 6 years later, you’re regulating the world of 6 years ago, and the world has moved on. Of course, it’s still useful, and there’s a lot of useful thought that went into it, but if you’re at this bleeding edge of the innovation and of science, it’s not always as useful. So you need a lot more than just the legal tools and the policy tools. That’s not to say that lawyers don’t do that. There are amazing and smart lawyers that are able to do that.

But I wanted to go study it, so I went to do a PhD, and I came to Oxford, and I told them, hey, I sense a problem here, I don’t know what to do about it, the law is not catching up with technology enough, and I think there’s something interesting there. And as we were talking, they said that I was asking philosophical questions. I wasn’t aware of that, I’d never really looked into philosophy much at the time, but the philosophy department took me under their wing and showed me how to formulate philosophical questions and then answer them and deal with them in practice. And my focus had always been, you know, computer science, research, consumer products, but it’s sort of in a digital sphere, and of course, you know, the future of music and that kind of content.

So then I went to Google. When I joined Google on my first day, I was greeted by the head of machine learning, and she said, yeah, I know we need ethicists, I don’t really know what ethicists do, so can you go figure that out, take 6, 12 months, do as many projects as you can. Report back to me after that, and then we’ll sort of make your job description out of what did work, and we’ll just forget the things that didn’t work.

So I think that that’s sort of what I’m coming to present here. It’s a bit of a reflection of the types of things that I used to say to people at Google, and this would range from, you know, people working on the YouTube algorithm, all the way down to people trying to figure out the next step of machine learning and generative AI and those things.

So it’s very applied product development all the way down to relatively fundamental research, and everything in between. And what I typically did was… Me talking at people with philosophical words didn’t really help anyone. So I just started drawing graphs, and I noticed that as you draw graphs and make other people draw graphs, you can actually create an interdisciplinary understanding that is of much higher value than, you know, a 45-minute talk using words that the audience might not fully understand.

So here’s one I drew, which tried to sort of justify my own job at the time, and here you see, you know, the line of technology going up exponentially, and the line of the law, being above technology, but then, so that inflection point is around the late 90s, early 2000s. That’s when we noticed that, actually, technology was moving so fast that the lawyers and legislators were trying to keep up. Doing a good job in some respects, but because technology was moving so fast, you had that gap between the two.

So here’s one I drew, which tried to sort of justify my own job at the time, and here you see, you know, the line of technology going up exponentially, and the line of the law, being above technology, but then, so that inflection point is around the late 90s, early 2000s. That’s when we noticed that, actually, technology was moving so fast that the lawyers and legislators were trying to keep up. Doing a good job in some respects, but because technology was moving so fast, you had that gap between the two.

And I would always argue that, you know, I worked with lawyers, but I did that bit working with the engineers to try and understand, you know, what really are their intentions, and what really is the context that they will be operating in, and how can we understand that the needs and the interests of the stakeholders, broadly conceived. and then translate that back into technology.

And that’s what I hope to talk about today, as well.

I’ll be very interested to hear how relevant it is for science. I think the new venture I’m exploring at the moment is about that. It’s a response to the Draghi report [Draghi report on EU competitiveness, 2024], I’m not sure if you’ve read that, it’s an EU-commissioned report by a former Italian politician. He said, basically, Europe has missed out on, you know, the internet economy and the social media and the AI economies, but maybe our next step should be the deep tech, so the science-based business models, where companies are encouraged to advance science and build business models around them. And I think that’s a particularly interesting thing to explore, being a European, being over there, and trying to see how these types of ways of thinking might be useful for that potentially new industry.

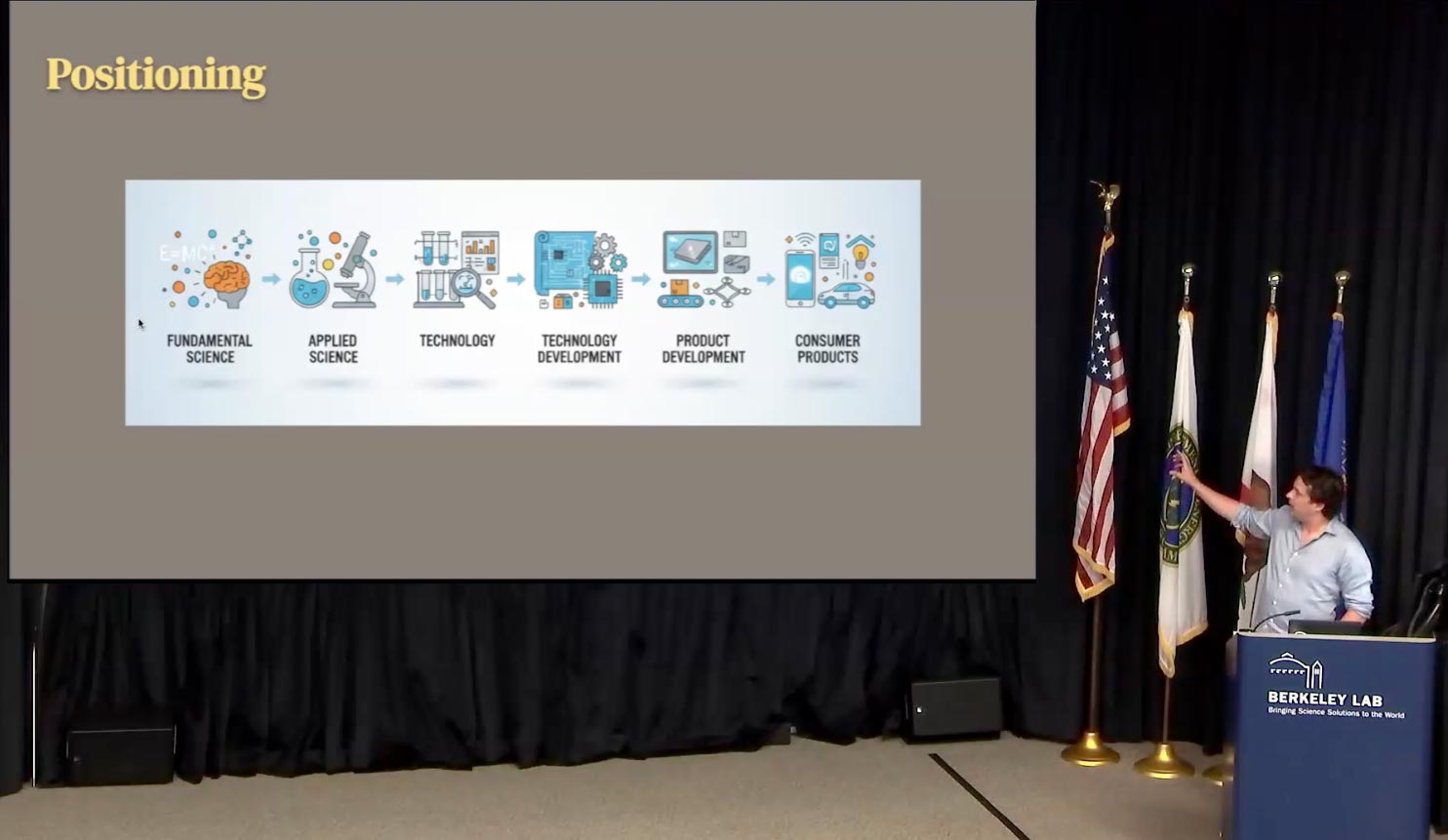

So here’s, you know, I’m sure you’ve seen many graphs like these. All I wanted to say here is that I’ve been working mostly, sort of, from the middle to the right in the last 5-6 years, and I’m sure all of you are mostly on the left side of that graph.

So here’s, you know, I’m sure you’ve seen many graphs like these. All I wanted to say here is that I’ve been working mostly, sort of, from the middle to the right in the last 5-6 years, and I’m sure all of you are mostly on the left side of that graph.

I have done a lot with applied science, especially with machine learning research. I don’t have as much experience in fundamental science and the ethics and sort of philosophy around that. So, you know, that’s to come, but I think there’s a lot from here that will be useful to inform that part over there.

Just a few things on what this talk is not about. I think these are all very useful things to mention, but just to sort of get them out of the way.

Just a few things on what this talk is not about. I think these are all very useful things to mention, but just to sort of get them out of the way.

- It’s not about the ethics of using AI to write your papers. I’m sure you’ve all had similar experiences where you peer review a paper, and it’s quite clearly written by an LLM [large language model]. You might even have questions of, you know, how can I help you further? And it’s, yeah, it’s quite frustrating as a peer reviewer.

- It’s also not about research ethics. My PhD was on that, but, that’s maybe for another time.

- It’s also not about LLMs as ideation partners, although I do think that’s a particularly interesting use case of large language models in science, if done well, of course.

- And it’s also not about dual-use concerns. I’m sure that’s something that’s on top of your mind at all times.

You know, I think we can all agree that all tools can be used for good and for bad, and that you can figure out ways to not do the bad things, or not encourage the bad things, and incentivize the good things.

I think some examples that I’ve been thinking about as I was trying to think what would be useful to talk about at the Berkeley Lab, there’s things like:

- Biotech: DeepMind’s AlphaFold, there’s this European company called Cradle, particularly interesting use cases of generative AI, trying to figure out, you know, how are proteins actually shaped, how can we shape new ones, how can we understand science based on proteins, and accelerate that significantly.

- Then the materials projects here at Berkeley [Berkeley Lab’s Materials Project], I think is a particularly interesting use case for the types of technologies I’m thinking about.

- And then, slightly more hypothetical, but we heard about this at the conference when Nathalie and I met, just the use of AI systems to manage resource allocation in settlements on other celestial bodies. Blew my mind when I heard about that, but I really thought that’s a perfect use case for the types of things that I’d like to talk about here.

Okay, so… I’ve divided this talk into 3 parts.

The first part is a slightly more elaborate version of what I typically say to a team at Google when we start working together. The second part is going to be about some typical responses to that, and then the third part is about the method that we set up at Google to help engineers and scientists think more clearly about what it is that they’re doing.

So, I’ve called this [first part] the “Grand theories of thinking differently about science and technology.” When I put this together, I felt like this guy, I’m not sure if you know this show, it’s a funny show, and “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia,” I think, but this is really what it feels like when you’re grappling with the history of philosophy and how we’ve talked about technology and science over the years. So bear with me if it doesn’t make full sense.

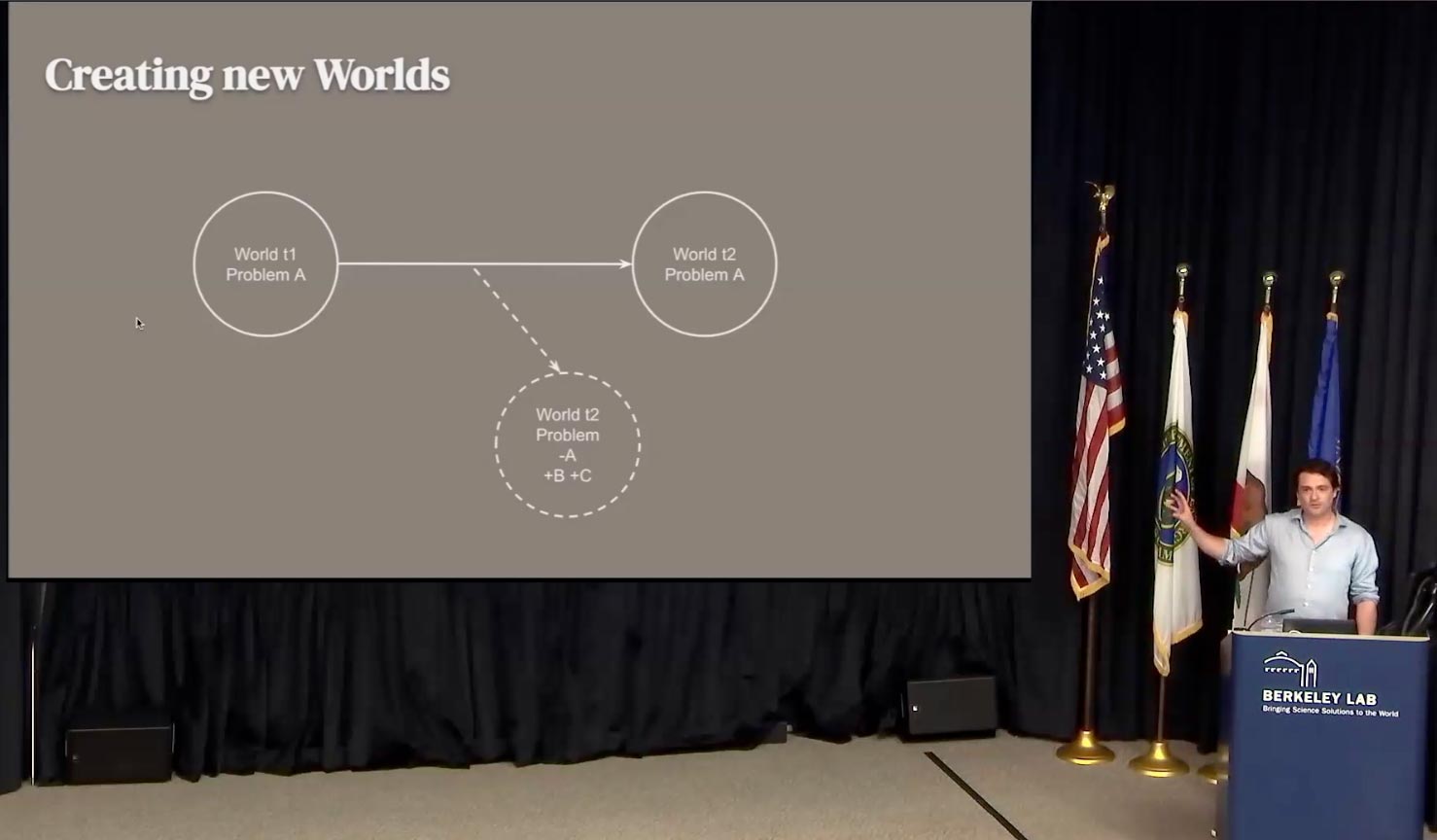

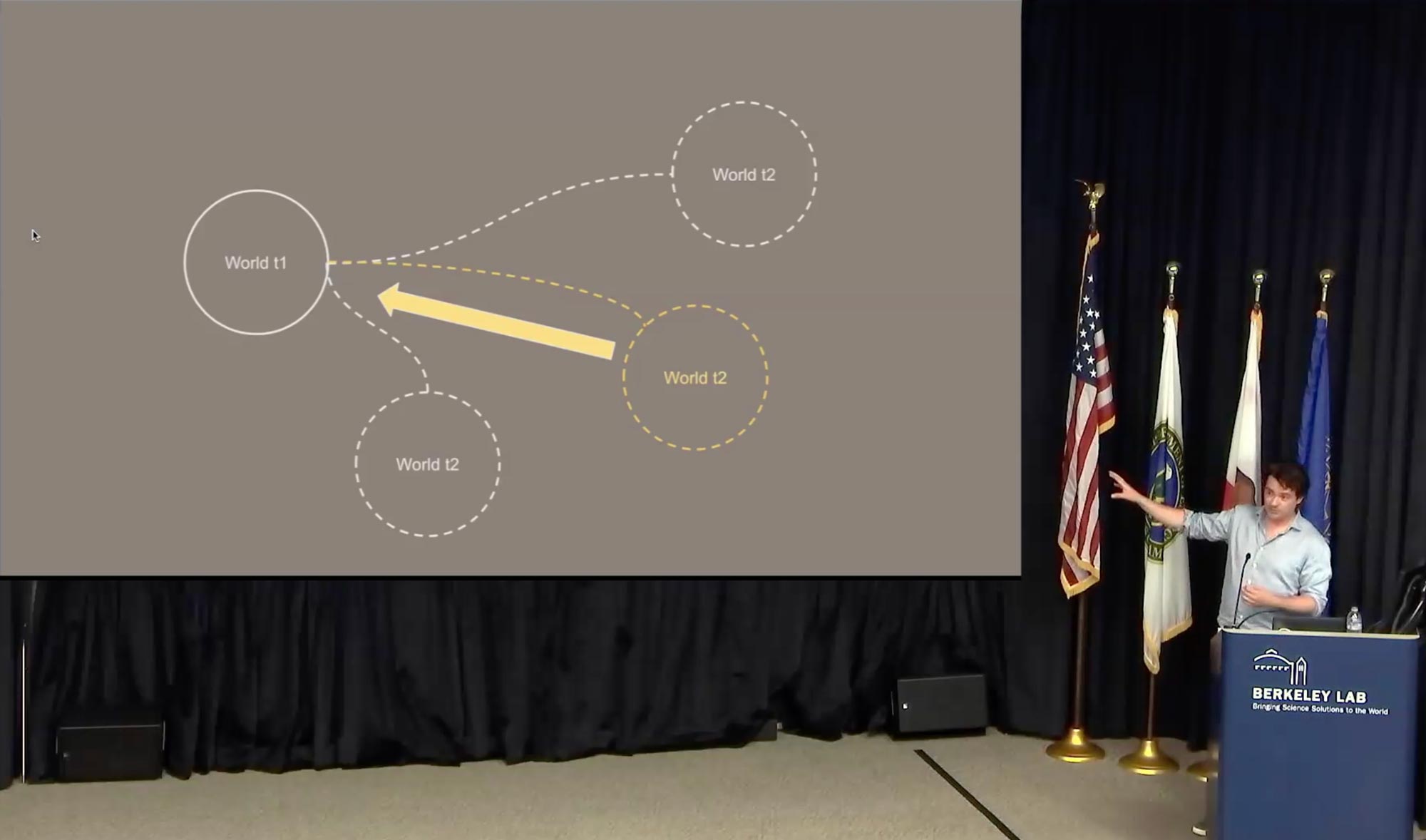

But it all comes down to this little graph, and this is a graph I’d always show to engineers and scientists. It’s super simple. So there’s a world at time point 1, and there’s a problem in that world; and then if you don’t do anything, you get to the world at time point two, and the problem persists, that’s obvious. But it’s typically the problem that motivates scientists and engineers.

But it all comes down to this little graph, and this is a graph I’d always show to engineers and scientists. It’s super simple. So there’s a world at time point 1, and there’s a problem in that world; and then if you don’t do anything, you get to the world at time point two, and the problem persists, that’s obvious. But it’s typically the problem that motivates scientists and engineers.

So what then happens is they intervene, and they are working to create a new world. And in that new world, at time point 2, you may have addressed problem A, but in the meantime, you’ve also created problem B and C, and all the way down the line.

And I always say to the engineers that I’m actually not working on their technology. It doesn’t matter too much what their technology is like when we start out working.

It is that world that we’re scrutinizing. We are trying to imagine the different types of worlds that they could be making, and why those worlds are the right ones to be making.

I’ll go into a lot more detail of that in a second, but this is always a trigger for engineers to stop thinking about their technology as an end, so as something to work on and then launch and move on to the next thing. But it’s a trigger to think of their technology as a means to an end, and the end is you’re actually having a huge impact on the world at various scales.

So let’s think about that, and then reason backwards to what we ought to be doing today to create the world that we want to create.

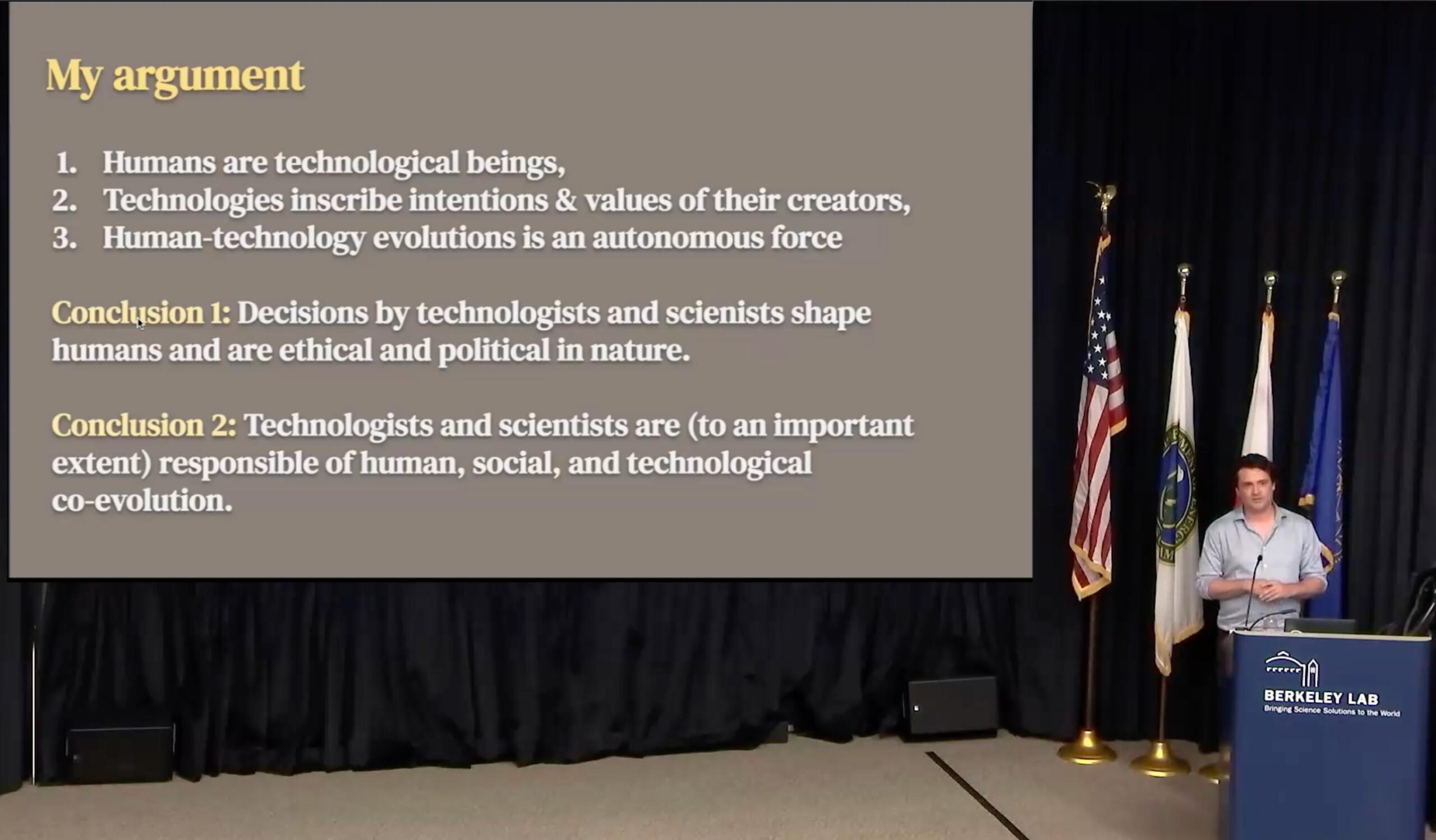

Okay, so I’ll just, you know, as a philosopher, you need an argument, of course, and this is sort of the basic structure of it.

- So first of all… My first premise is that humans are technological beings. Since the moment that we started building axes, you know, we shaped technologies,

- And in turn, they shaped us in our societies. The technologies we build inscribe the intentions and values of their creators.

- Third premise is that human technology evolution is an autonomous force. It’s very hard as individuals to stop the force of technical development.

So therefore, the decisions by technologists and scientists actually shape humans’ worlds, in practice, and therefore, technologists and scientists are, at least in part, but to an important extent, responsible for human social and technical coevolution.

I’m not sure if you fully agree with this, but I’m gonna try and make my point. I’m happy if you don’t, and it might be a good discussion. But I think this is an important point for at least people who are building consumer technologies at Google scale to really take on board that you’re not just building a cool new technology, you’re really reshaping how people relate to each other, to information, how they shape beliefs about the world, or how they don’t shape beliefs about the world.

Okay, so what you see here is, I’ll go through some theories, and these are images that, they’re not direct copies, but they’re the types of images we’d used to make with engineers at Google. So we’d go through a particular theory, and we’d ask them to draw it out, and these are the types of things that they would have drawn. I don’t have access to the originals, so I tried to recreate them as best I could. But it’s a really interesting way of interdisciplinary dialogue to ask someone not to repeat what you said, but to, you know, make a graph or diagram drawing, and then to discuss the merits of each.

Okay, so, Bernard Stiegler said that, you know, the thing I mentioned earlier, humans and technology always shape each other, and Donna Haraway – I think she was actually a Berkeley philosopher, if I’m not mistaken – but she went a step further, and she said that, you know, it’s the cyborgs, it’s the human who’s onboarded technology onto their being, is actually a better analytical lens for social, political, and bodily realities, better than just thinking of humans as humans by themselves.

So if you want to create these analyses from the humanities, you really are to think of humans as being a technical being.

Now, technologies shape beliefs and relationships. Don Eidey wrote in the late 70s, that humans will always use technologies to engage with their environment, and Peter Paul Verbeek later said that technologies are actually proactive mediators of humans and their world.

So it’s really interesting to think that, you know, these technologies don’t just have a particular function, they actually define the way that we engage with our world.

So creators inscribe values into their technologies. Langdon Winner wrote two particularly interesting papers. Are you familiar with these types of authors? I see a few nods, okay. So Langdon Winner asked the question, and then in a long paper, basically answered, yes, do artifacts have politics [Do Artifacts Have Politics?, 1980]. He gave a range of examples of how artifacts can be used in the world for very political ends, and if you think about it, you know, many of the technologies we have in our hands also have some sort of politics.

Later, he wrote a paper [Technologies as Forms of Life, 1983], where he warned that actually we are “sleepwalking” through the process of reconstituting the conditions of human existence. We might go to vote every four years, or every 2 years, whatever it might be, wherever you are, but you’re not voting on, you know, what the new iPhone should look like, or what the new particle accelerator should be doing. You’re voting on social policies, and the technical world is… it has politics, but it’s allowed to evolve in its own way.

Of course, there are market forces and things like that, but still, the control that individuals have, and groups of society have, over the trajectory of technology and science is something that we’re not fully aware of and are just accepting. That’s not to say that it’s a bad thing, but it’s good to realize.

Other writers would then talk about, that there’s some unintended conformity to the logic of technology and science. Andrew Feenberg argued [Critical Theory of Technology, 1991] that there’s a particular technical code inscribed, obviously, in technologies, but also in the sciences that underpin those technologies, and those codes might be, you know, speed and efficiency and scalability of systems, and then others… and Feenberg would then say that, you know, users are actually asked to conform to that: If you want to participate in this fast-moving technical and scientific world, as humans, you have to adapt to the demands of the systems, the logic of those systems.

Others then argued further that it’s starting to replace and change our reasoning. So we might, have our own preferences and interests, but actually, if you’re engaging in this fast-moving world, this Frankfurt School – the set of German philosophers and sociologists – they called it, that where humans are developing this instrumental reason and this technological reality, obviously, when everything’s mediated by technology, that’s a consequence of that. And then they went as far as saying, you know, technology is a tool of domination, it can be used by those in power, on purpose or inadvertently, to dominate humans and to make sure they act in the ways that they want.

Now, the last, slide, you know, this is the sort of the doom slide. Even in, in 1954, Jacques Ellul – this is a book [The Technological Society, 1954] that’s being rediscovered at the moment. There’s a lot of podcasts about this, because 60, 70 years ago – 80 years? a long time ago – Jacques Ellul already predicted, basically, what’s happening today, and he’s saying that, basically, technology is the totality of methods that have been rationally arrived at based on this idea of absolute efficiency, and that, in turn, is becoming an autonomous and inescapable force that is self-augmenting, and we humans have actually lost control of where it’s going. If… I just drove through San Francisco on the way here, all the billboards are about AI taking over your workforce, and so I think that’s exactly what Jacques Ellul was saying in the 1950s, that the way we are going, it’s, you know, it’s got its own logic, its own path, it’s inescapable, and we are subjected to it.

Okay, and then I have one more slide, actually. Heidegger in the same year, controversial figure, but wrote some interesting philosophy. What he said is that, as we become more technically proficient, and as we, conduct more science, we are creating a lens based on all the other things, a lens that is forcing us to see the world, but also ourselves as a collection of resources to be managed and to be optimized for certain things, might be for efficiency, or might be for something else. And what he then says – and I think this is an important pivot back to ethics – is that, “The essence of technology is nothing technological,” and what he means by that is that the force that technology has on humans, and on societies, and on the way we reason and think and act, is not actually about the mechanisms of the technology, it’s about the impact that it has on everyone.

So if you want to study a technology, you have to study the impact and not the mechanism of the technology.

So this was me putting all the strands together. I hope it made some sense, this argument. And yeah, and the very, sort of, basics of it, and this is what I would typically drive home to Google engineers, is that the tech that you’re developing actually reflects your intentions, you know, the problems you choose to solve, the ones you don’t choose to solve, the ones you think are worthy of solving by technological means. Ought they be solved by technological means? Those are all intentions, and there’s a lot more.

And then as you are inscribing your intentions into the technologies, you are shaping the beliefs and the relationships of millions and billions of users, so you are changing the world with your intentions, so let’s criticize those, or let’s examine them, examine them critically, and not just look at, you know, is the technology fair or not?

I just have a quick reflection. I was at this conference at Stanford last week, it was an AI safety conference, and I thought it was exemplary for what I’m trying to explain here. Great conference, wonderful engineers and people from inside and outside the university coming together to talk about this idea of safety in AI, and what I noticed was that almost everyone was talking about safety as a reliability or robustness issue. Can drones find their way, and will they harm people when they fly, for example, or can trucks drive safely through streets.

But I was arguing that actually it should be AI safety as social impact, and not as just a technical issue, and the reason is that I think there’s three key harms that we see with, you know, generative AI moving into our world now, that autonomous force:

- We have a loss of a shared reality. You know, people can start creating their own realities. We can really easily create mis- and disinformation and spread it very quickly, and make it believable. We can even adapt it to these inferred social demographics of the people that read certain things. So we are in the process of losing that shared reality.

- Also, by using AI tools increasingly, people have noticed a cognitive decay that’s starting to happen, people are exercising their memory less, their critical reasoning skills, and if you take that from an individual to the social plane, then we’ll have, you know, society-wide cognitive decay, which is likely a huge issue.

- And then, of course, just job loss. I think it was the OpenAI CEO, of course, a bit of a hype man, but he said that in the next 5 years, 40% of jobs will be replaced. I don’t believe that, but, you know, that’s the sort of thing that this autonomous force is working towards.

And none of these are reliability or robustness issues. So, it was quite eye-opening to say that at the conference, and then hear the responses that people came to me and said that they hadn’t thought about their technologies in this particular way. They always just thought that they had to solve for reliability and robustness. So yeah, that’s the point there.

But so these, these philosophers that I mentioned, they’re not just doomsayers. They see themselves as diagnosing the issues that they’ve been seeing in the world, and they write their papers not to scare people, but to call people to action. So, a typical thing that they’ll say is, or here are a few:

- Donna Haraway said, you know, she’d actually rather be a cyborg than a Greek goddess, because she prefers the control that she has over which technologies to, and not to, include in her life. There’s a wider argument there.

- Someone else said that, you know, we’ve diagnosed this problem, and actually what we need is more democratic rationalization about the trajectory of science and technology.

- And Heidegger really wrote a very doom-type paper about technology, but he said that, you know, once we understand this, we need to pay heed to the essence of technology, and not just only focus on the efficiency paradigm of technology.

So, yeah, all of that is to say, or to summarize, I think, to some extent, by this super simple graph, that, it’s the hypothetical world that you’re creating that needs to be scrutinized, and from there, you can scrutinize the mechanisms of technology and science to see whether you’re actually on the path of where you want to be.

But if there are questions or criticisms, super happy to take them. Okay, so we’ll move to… yes?

[Question from the audience]: Yeah, thank you for your thoughtful remarks. Just had a question on your starting point, which is that man and women, people are technological beings. I’m just wondering. That seems to be a very narrow starting point. If you started with a different starting point, or a hypothesis such as man is, all men or women are philosophers, or all people are social beings, would you come to the same conclusions? Or, I’m just curious, why start where you started. Thank you.

Ben Zevenbergen: Yeah, I think the argument is that humans are indeed social beings, but that the sociality is being mediated by technologies. If that weren’t the case, you know, we probably wouldn’t be in a building like this, with clothes and laptops and screens. So, the way we conduct our social life is determined by technology, to a large extent. Of course, there’s that feedback loop that we then determine the way that technology ought to develop, and which technologies we do and don’t use. But it goes down that one step below and says, you know, sociality is actually a product of technology. Maybe we can talk about it afterwards.

So I just want to move into this, the sort of theories about controlling technology, and David Collingridge in the 80s actually wrote the dilemma very nicely [Social Control of Technology, 1980]. I won’t read out the full thing, but what he says is that (I think this bottom part’s the important part) so “when change is easy” – so when a technology is being developed, you haven’t launched it yet – the need for changes to that cannot be foreseen easily. But “when the need for change is apparent” – so when people are actually using your technologies, or they’re, you know, they’re dominated, according to some of those theories – change may have become “expensive, difficult, and time-consuming.”

So I just want to move into this, the sort of theories about controlling technology, and David Collingridge in the 80s actually wrote the dilemma very nicely [Social Control of Technology, 1980]. I won’t read out the full thing, but what he says is that (I think this bottom part’s the important part) so “when change is easy” – so when a technology is being developed, you haven’t launched it yet – the need for changes to that cannot be foreseen easily. But “when the need for change is apparent” – so when people are actually using your technologies, or they’re, you know, they’re dominated, according to some of those theories – change may have become “expensive, difficult, and time-consuming.”

Of course, in 2025, that might be somewhat different, because a lot of the technologies we have today are on cloud servers, where it’s easier to change them. But still, this dilemma holds true also for the work that I was doing at Google. That you wanted to be there as early as possible, and you wanted to do the hard work of trying to understand, what is this technology going to do with the world, and is that what we want it to do.

You’d never be right, of course. You’re always surprised about how people do and don’t use certain technologies. But it was a best effort thing, and we had a lot of people working on this. And I’ll show you how we did that in a moment.

Okay, so some typical responses… I’ll keep this part very short.

So if you’re thinking about ethical considerations, about how to build technologies, there are two ways, I think, that you can go about it.

You can say top-down, you know, the directors, or the CEO, or whoever it might be, might say, these are the contours within which we are operating.

And then there’s this bottom-up idea, which is shaping the culture of those who are building the technologies.

Going to the top one first.

So you’ve got these principled approaches, there are many websites that collect AI principles and policy documents and whatnot – I think this is UNESCO (Global AI Ethics and Governance Observatory), here is the OECD (the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence) – wonderful websites. It shows you how people around the world are trying to implement these top-down communications, really sort of creating a bottom line of what is acceptable behavior and hoping that people will adhere to that. Typically, you will then have review committees that people build something for a while, and then pre-launch or pre-funding in the scientific realm, it’ll be checked whether, indeed, you are living up to those principles, yes or no.

In Canada, you’ve got this initiative. Do you know what they’re doing here, any chance? They’re showing rings [Iron Ring]. So if you graduate as an engineer in Canada, I understand, you get a ring, and it used to be that the metal from that ring was from a bridge that collapsed due to engineering, laziness I guess you could call it, where they didn’t live up to their own codes of conduct. So it’s a reminder, and it’s on the pinky, that whenever you’re writing on a desk, you hear the [click] the thing, as a reminder of, like, you have a social duty. But still, these are codes of conduct and review committees pre-launch, and they hope that people adhere to certain rules, and if they don’t, I’ve seen many cases where it’s, you know, sadly let through.

I think in science it’s a bit stricter than in technology companies.

So what we then did at Google was we solved the problem of people working on a project for two years, say, trying to launch it. Other ethicists would then come with their thumbs up or thumbs-down decision. If it’s a thumbs-down decision, you’ve upset a whole team of engineers, they’ve wasted two years of their career, so it doesn’t yield the best engineering-ethics collaboration over time.

So what we tried to do is this, really this sort of bottom-up approach. The top-down was in place. It was fine, it wasn’t very popular, but it did its job to some extent. But what we try to do is really work with the engineers to give them the tools to take direct responsibilities as engineers, who are developing tools for millions and millions of people.

So we called it moral imagination based on this theory from the 1990s. It has a longer history, I’ll show you that in a moment. Patricia Werhane defines the method of moral imagination as accepting that your own perspectives are always going to be limited [Moral Imagination and Management Decision-making, 1999]. It doesn’t matter if you’re a team of, you know, 25 engineers and scientists – you might even be from India and Japan and America and the Netherlands – it doesn’t matter because the background that people typically have in these teams is very similar, you’ve learned a very similar language of identifying and solving problems.

So, she invites people who are building technologies, or who are making big business decisions to broaden that scope. And to do that, you have to actually – I don’t want to say open your mind, but in some ways, that is what I’m trying to say – so as a group, you have to be able to imagine different alternatives to the thing that you’re trying to do. Try to understand different viewpoints critically and actively engage with those and see if it comes up with new considerations for the work that you’re doing; or with new approaches, maybe it gives you signals that you probably ought not to be doing something.

I’ll go into how we operationalize that in a moment, but there’s the long history of this. I won’t go through each theory, but in philosophy and ethics, people throughout the ages have said that you really need to be able to take a step back, two steps back, lose your identity, lose your ego, take an as objective position as possible, and evaluate the choices that you’re making. Of course, we all know that’s impossible as humans, we’re all subjective in how we experience the world, but there are steps that you can take to do that.

Particularly interesting here is John Dewey’s in 1934. He described ethics as an art form, and not a science. So, you know, he’s saying that 1 plus 1 doesn’t equal 2 in ethics. It’s not something that you can calculate. There’s not a, you know, top 3 things you ought to do, and then you’re ethical. He says it’s a “dramatic rehearsal” of trying to understand how people would object to the thing that you’re trying to, that you’re proposing, and then responding to that, and seeing whether your own position holds.

I’ll skip that one. [skipped slide]

So, ethics has been defined in this particularly interesting way by Peter Singer. He says that, “The notion of living according to ethical standards is tied up with the notion of defending the way one is living,” giving reason for it, and justifying it. You can replace that with, you know, the notion of building technologies in an ethical way, or conducting science in an ethical way, is tied up with the notion of defending one is conducting the science, setting up the experiments, giving reason for and justifying it.

And that goes back to understanding or being able to incorporate objections and different worldviews into your setup, and describing why the way that you are developing a technology is the right way to go about it. Yeah, so it’s giving that sort of transparency of the world that you’re trying to create with the technology, and not just saying, well, this is a cool tech, and therefore we’re launching it, which you see quite often on billboards in San Francisco.

This quote you’ve probably heard of, Socrates, Plato, saying that “the unexamined life is not worth living.“

I once said at Google that the unexamined technology is not worth building, and that really resonated in some funny way.

So I’m curious if this sentence would resonate with you: Is the unexamined scientific research is not worth pursuing? And by that, I mean not just, you know, is it scientifically excellent, but what is actually going to be the first, second, and third order downstream consequences of developing this particular set of knowledge. I’m curious.

So we’ve been contributing to this literature on moral imagination. There are two papers that we wrote [Engaging engineering teams through moral imagination: a bottom-up approach for responsible innovation and ethical culture change in technology companies, AI and Ethics, 2023; and Moral Imagination for Engineering Teams: The Technomoral Scenario, International Review of Information Ethics, 2024] – there are two more in the pipeline at the moment, happy to share those if you’re interested – and what we try to do is make people think far more critically about applying ethics to their work.

- So we typically would start with the thing we did at the beginning, you know:

Making sure that people see technology as socio-technical and not just as a technology (again, that quote, technology is nothing technological), - Doing deep dives into stakeholder needs and interests, and really informing the way that product and research teams at Google would engage with the people whose lives that they’re affecting. I think that… I wonder how you would do that in science, but I think there might be ways to do that, too.

- And then giving people the tools to really critically evaluate design options.

Most of the time, those evaluations would be, again, on things like efficiency, or, you know, does user uptake go up, kind of figures. And we said, that’s simply not enough, and we had a lot of teams that started adopting their own developed, more ethically informed evaluations for which option they should take.

Okay, so I’ll go through how we’d set up these [Moral Imagination / Ethical Awareness] workshops. These are typically week-long engagements where we’d have about, 8 to 12 hours of touchpoints with the teams, and we’d take them from knowing basically nothing about ethics to being able to talk about their technology and the various options that they have in ethically informed ways.

You know, they didn’t come out as philosophers at the end, but at least we created a culture within the team that allowed someone to raise an objection to what’s happening, give reasons for it, try to, you know, defend it, and then the team would see whether that’s a justifiable objection, or whether actually they were on the right path, or there might be another point of view.

So you, you start these engagements, about two and a half, three hours of just talking about the ethical awareness of the team, and we did that usually in sneaky ways. We’d ask them, you know, why are you on this particular team? Why are you not on the YouTube team? Why are you not working in the Berkeley Lab? Or why are you not, you know, a singer-songwriter? Why are you choosing to do this?

So the team would then formulate their answers, and as they’re explaining what motivates them to work on this thing, the facilitators take a lot of notes on basically what’s being said, and trying to parse out the ethically relevant points that are being made. And we have a few more questions like that.

By the end of about an hour, an hour and a half of a discussion like that, we teach them a little bit about what ethical values are, and then we reveal the things that they’ve said, and we ask them to label the ethical values and everything.

And it’s fascinating, because there’s a huge sheet with lots and lots of words, their own words, and when they start labeling, typically there’ll be about, you know, 40, 50, something 60 different ethical values that the team themselves are discovering is motivating their own work.

And then we do this negotiation of trying to find, you know, what are the top 4 or 5 values that really ought to guide this work. Again, be 45 minutes, an hour-long discussion of trying to create the ethical lens of, you know, what actually matters most. When we make decisions in future, what are the values that ought to govern our decisions?

And this is still sort of very much at the beginning, but just making people grapple with that, and taking them out of that logic of efficiency and scalability, and into the socio-technical logic of what they’re doing.

These are the types of graphs we would give them. We have several other graphs. But we’d ask them to first define… here, for example, we have privacy… really find a definition of the ethical value of privacy, and then make it relevant in the context of your own work.

These are the types of graphs we would give them. We have several other graphs. But we’d ask them to first define… here, for example, we have privacy… really find a definition of the ethical value of privacy, and then make it relevant in the context of your own work.

So people would go to Wikipedia, or some philosophy encyclopedia, whatever it might be, find those definitions, grapple with them, and then discuss them. And in those discussions, we draw graphs like these and show that people actually have very different conceptions of the lovely words that they’re using. A team might say that privacy is really important, but person number 1 might see it as the right to control your information, whereas person number 2 doesn’t see it as control, but more as the right to be left alone from interference of others. And then number 3 might say that, you know, the reason we have privacy is because it’s a social good, it allows a society to function, whereas number 2 would say, like, oh, no, actually, it’s an individual right, and, you know, the social nature of it actually doesn’t matter too much.

We could talk about privacy forever, but the issue here is that by drawing a graph like this, you support the conversation. So this is not a scientific representation of the value of privacy, but people are able to point at where they are on the spectrum, and how they actually understand it.

[Question from the audience]: Are those emergent?

Ben Zevenbergen: Yes, yes. [Unintelligible question from the audience] Oh, whether the polls are emergent from the workshop, right? the answer is yes. So we, as we are going through definitions and interpretations of those definitions, you start to see those polls typically emerge.

Sometimes it’s a bit harder than other times, but it’s a useful exercise to understand, and then you can use this as a way to make people stand up and point and say, I think we’re here, and someone else says, I think we’re here. If you don’t have a graph like this, it’s much harder, because people have these strong attachments to how they see particular ethical values and are not able to conceptualize other ways of seeing them, especially if they’re not trained as ethicists or lawyers.

So these types of graphs, again, are so useful for interdisciplinary discussions on the socio-technical aspects of this type of work.

So, once we’ve gotten an understanding of which ethical values should guide our work, we get to the phase of deliberation. Typically, ethical values are not always compatible. They will be in tension either immediately or down the line. I’ll show some examples of that in a moment. And we really try to tease those out.

So we use, I generated a nice picture for you of where we get people to think or apply science fiction to their own work, and put it 5 or 10 years into the future, and deliberate that future.

So we use, I generated a nice picture for you of where we get people to think or apply science fiction to their own work, and put it 5 or 10 years into the future, and deliberate that future.

At Google, we have the luxury of lots of science fiction writers working at the company, who met with our team once in a week, and we’d explain to them the technology that we’re scrutinizing the week after that, and they would then, help us come up with a scenario that places it in the future, and just puts in these little ethics Easter eggs nuggets all across the scenarios, so that then the team would be taken out of their day-to-day reality, get to imagine some hypothetical future world of where something like their technology is launched and then role-play that in certain prescribed roles.

And we typically have people take on roles that they’re least comfortable with so that they’re not just saying the things that they would be saying anyway, but that they really need to grapple with creating arguments and coming up with interpretations and reasons for certain ethical values.

And that would then typically, again, this would take an hour or so to understand the scenario, prepare your positions, and do that discussion. And at the end of the discussion, you reflect on the discussion that was had, and you tease out all the ethical tensions, that were apparent. So if you start with a set of 4 or 5 ethical values that guide the thing, you probably end up with about 20 tensions between those values that might manifest in different ways.

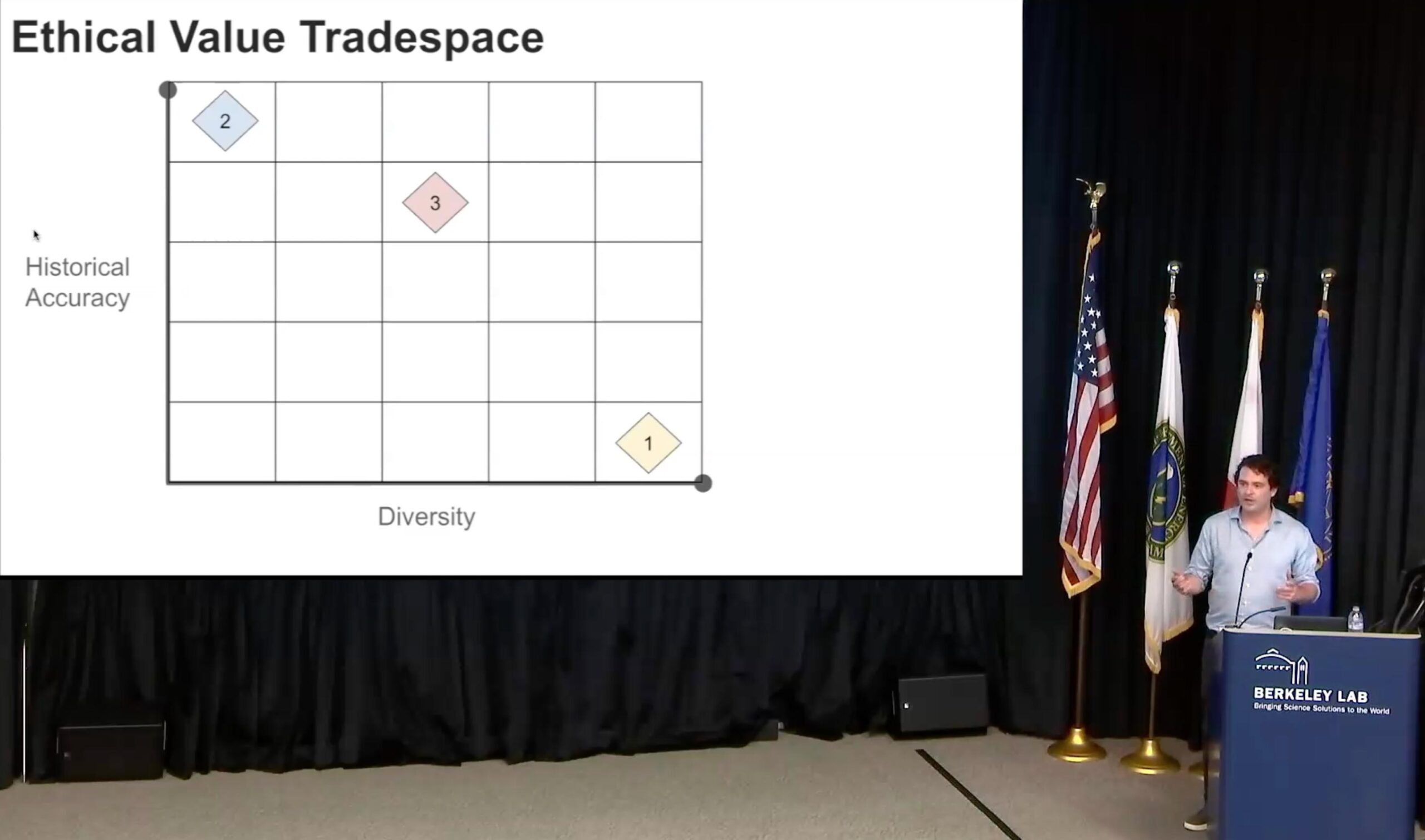

So here’s one way that we would talk about this. This is actually an example of a retrospective we did. I’m not sure if you remember when Google launched a text-to-image product. Of course, people start to try and break it in the public, and, someone typed in the very simple words, “show me a picture of the founding fathers of the United States,” and out came a picture of a diverse group of people. I think it was men but of different skin colors, but it could have also been women, I can’t quite remember, which is, you know, it’s interesting that it’s done that way. There’s some underlying ethical considerations of we want diversity in our representations, but if you’re creating historically relevant pictures, that might not actually be what you want to do. You are probably rewriting history in that way.

So here’s one way that we would talk about this. This is actually an example of a retrospective we did. I’m not sure if you remember when Google launched a text-to-image product. Of course, people start to try and break it in the public, and, someone typed in the very simple words, “show me a picture of the founding fathers of the United States,” and out came a picture of a diverse group of people. I think it was men but of different skin colors, but it could have also been women, I can’t quite remember, which is, you know, it’s interesting that it’s done that way. There’s some underlying ethical considerations of we want diversity in our representations, but if you’re creating historically relevant pictures, that might not actually be what you want to do. You are probably rewriting history in that way.

What it turned out was that pre-launch, someone had amped up the diversity parameter in the generations things after the reviews had been done, so that’s quite interesting that it happened.

So they were basically arguing about position one, that diversity is what matters. Of course, I didn’t think about historical accuracy at the time, but because that decision was made, historical accuracy was deemed as irrelevant.

So the reaction was strong, and people said, well, actually, when we’re talking about historical accuracy, diversity doesn’t matter, shouldn’t matter.

Now it’s, you know, we’re not actually creating photographs of what happened in the 15, 16, 1700s. They are generated AI images, and there is text around those tools saying, you know, this is for entertainment purposes, and things like that.

So, I’m not sure exactly where we concluded, I think it was around 3, but the point is, again, not that this is a graph based on data. The point is that you can point at different quadrants and say, you know, what does it mean to be here? How would we define diversity if we are at that position? Three. So we’re not going for the absolute value, we’re not going to neglect it completely. What does it mean if we’re in the middle, and we give a little bit more importance to historical accuracy, once we identify that there’s a historically relevant query being done.

And the interesting thing about graphs like these, again, like the previous one, is it allows that conversation to happen, and it allows people to point at something and say, I think if we’re here, then this would be the definition, and then technically it would mean this and this and this. And then someone else might point to the one next to it, and then you have a structured argument rather than a set of opinions and egos shouting in the room about their worldviews.

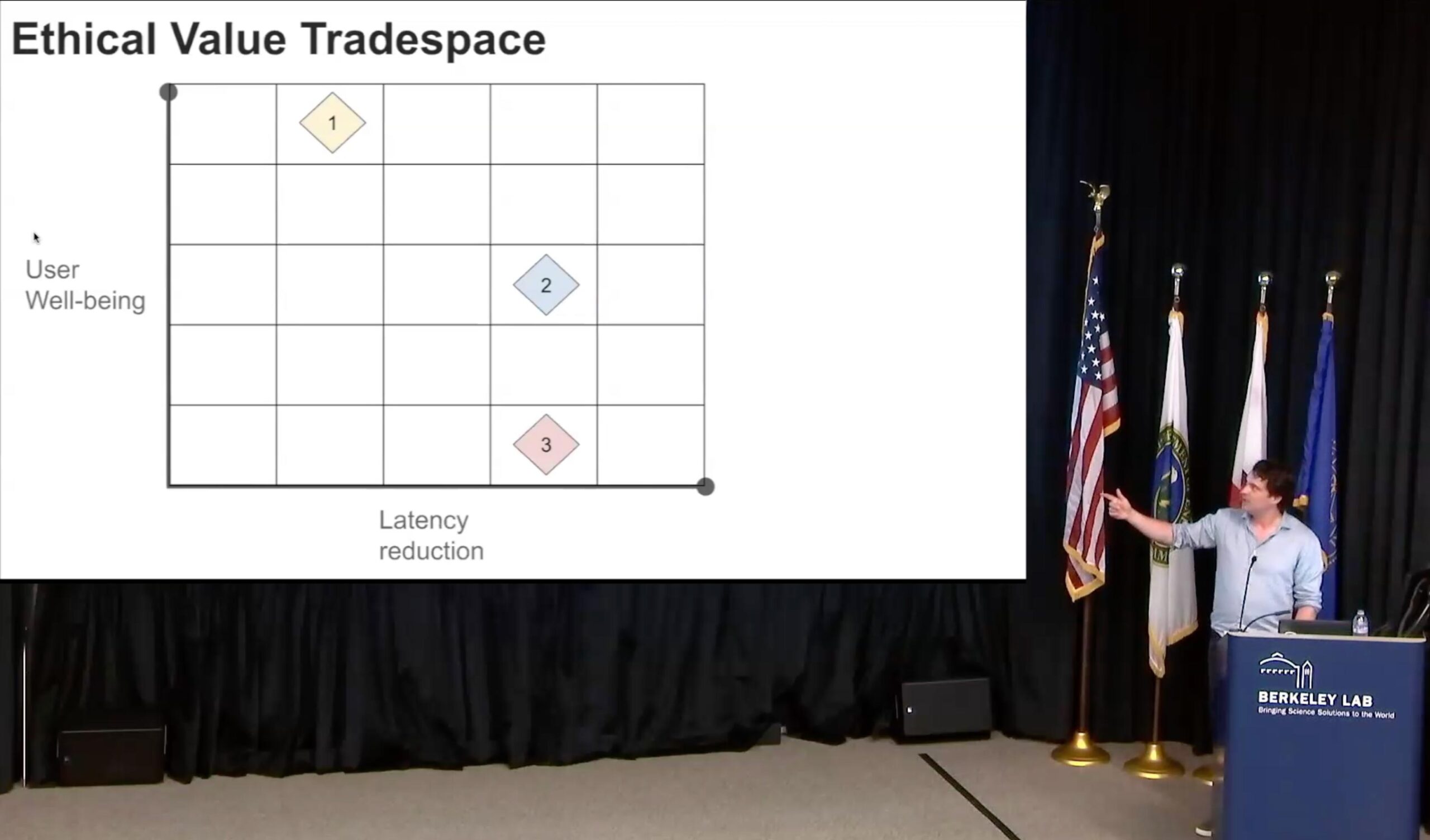

Yeah, we made many of these, and this is a very typical one, where latency reduction is sort of the efficiency value. And then user well-being is always this wonderful ethical term that people come up with, but they never really know what it means. We always ask people to, you know, pinpoint where in the technology stack a particular ethical value is uplifted, and user well-being is always the fun one, because people just don’t know.

Yeah, we made many of these, and this is a very typical one, where latency reduction is sort of the efficiency value. And then user well-being is always this wonderful ethical term that people come up with, but they never really know what it means. We always ask people to, you know, pinpoint where in the technology stack a particular ethical value is uplifted, and user well-being is always the fun one, because people just don’t know.

But when you start thinking about it critically, there’s a lot that you could do to uplift user well-being. You can do a lot of research and find out, how people respond, even. So neurological research shows how people respond to certain technologies, and you can adjust the things that you do within your technologies, based on the outcomes of that research. But then that would significantly reduce, or increase, actually, the latency, so your efficiency would go down a lot. And it’s really interesting to play around with these types of, you know, assumed goods. Reducing latency is always good at a company like Google. But actually, if you find something else important, let’s engage with that latency then, and let’s see where the trade-offs actually aught to be.

So I haven’t done these types of things in science, but I wonder whether things like this might be interesting to try out as well. It’s, it looks very simple, but the process of getting there is actually quite complex. (I’m not sure why this is here.)

Okay, so what we then do is the, so we get a better understanding of where we want to be in those graphs, and that allows us to better understand what the different worlds are that we might be working towards. You know, if you place user well-being at the top, you might be in that world. Or if you, you know, if you think historical accuracy is nonsense, you might be in that world. So as you progress on those graphs and create some sort of understanding of where it is that you want to work towards, you then pick a world, so it could be this world over here, and then that gives you the ammunition and the tools to work back to the current world and understand better what it is that you ought to do to get us there.

Okay, so what we then do is the, so we get a better understanding of where we want to be in those graphs, and that allows us to better understand what the different worlds are that we might be working towards. You know, if you place user well-being at the top, you might be in that world. Or if you, you know, if you think historical accuracy is nonsense, you might be in that world. So as you progress on those graphs and create some sort of understanding of where it is that you want to work towards, you then pick a world, so it could be this world over here, and then that gives you the ammunition and the tools to work back to the current world and understand better what it is that you ought to do to get us there.

[Question from the audience (inaudible)]: I wonder, …

Ben Zevenbergen: Absolutely, absolutely, yeah. Oh, yeah. So in the workshops, do we use historical examples of how engineers and scientists have responded to technological change in their lifetimes. That’s the question, yeah? Yeah, absolutely. So, I couldn’t go through all the steps of the workshop, because it’s just far too many, but one of them is, when we are thinking about particular values, we try to, you know, interpret it in the context within which we’re operating, and then we also try to understand how is this different from other technologies that we’ve seen in the last few years or decades. So a good example might be, you know how we’re adding cameras to glasses right now? And you can walk around and film everything, basically, and everyone. So the question was, like, what are some similar technologies? Well, Teslas, have had, were the first cars to have cameras everywhere. But the difference is, you don’t take your Tesla into the shared restroom. So, you know, what was appropriate for a car with cameras might not be an appropriate policy for glasses that can just walk around and engage with people. And so that’s how we like to just really find out what the uniqueness is of the thing that we’re working on, and what might inform it, and what information should actually be discarded because it’s too different. Yeah, it’s…Those discussions are a lot of fun. Yes, sorry. So,

[Question from the audience (microphone muffled)]: You know, the, on your… to go back to your thing about how to infuse engineering with that.

Ben Zevenbergen: Yes.

[Question from the audience, continued (microphone muffled)]: The, National Academy of Engineering had a very serious program on support workshops, so forth, about using engineering education… very thoughtful, and it actually had a big impact on the undergraduate…

Ben Zevenbergen: Nice.

[Question from the audience, continued (microphone muffled)]: … curriculum in engineering, but they’ve also realized that, in many of the companies, maybe 8% of their workforce comes from U.S. engineering …. and so, it actually has very low … and we’ve run into a similar thing in graduate programs in science, where, of course, there had been quite an effort on, on, research integrity, in science …, but then, at graduate programs, a very small fraction of those graduate students come from undergraduate programs. So, you have to, so the fact is, that we’re in a situation where, what you’re talking about, where the only point where these fees come into the U.S. program of science and technology is at a company. Well … and so, that’s the possibility to come sitting at that point, which is really difficult compared to, actually… addressing undergrad schools, and so it’s actually… I think that’s something that… the … engineering community. … I’ve been wrestling with that problem.

Ben Zevenbergen: Yeah, absolutely. So the reason… I did my postdoc at Princeton, and the reason was, because the head of engineering department and the head of philosophy decided to take this task seriously, and I happened to be walking around at the time, and I spoke to someone who knew someone, and I was put forward as the person to lead that effort, at least the exploratory part of the getting philosophy into engineering education. Now it’s being headed by Stephen Keltz, a colleague of mine, and he’s taking it to new levels, and it’s really great to see. Yeah, and part of the reason I was at Stanford last week was also these types of discussions, where the engineering school was really trying to figure out how to make this not just a, you know, here’s an overview of ethics, now good luck, but more of a, how can we make ethics actually tangible and part of the role description of engineers. So it’s an ongoing challenge, but yeah, it’s great to see, and I think the US is much further in this than Europe is, sadly.

I’ll just… Yeah, yeah, I’ll just do one last thing.

So, what typically happens is, at the end of this, we come up with a set of responsibility objectives. They might go into product requirement documents and shape the way technology’s built. They will shape user experience, research, questions, and surveys, so that they are actually more ethically informed about, you know, the ethical preferences of users. Evaluation criteria of a technology, you know, after it’s launched or before it’s launched, how… what metrics do we use to evaluate a technology? Is it just latency and efficiency, or is it something else? We contribute to clearer communication internally. My favorite ones were when teams asked for ammunition to say no, to not do a certain thing. You know, a vice president might say, like, oh, explore this, and then they deem it as unethical, so we worked with them for a week to figure out what it is, what they need to say, to justifiably refuse to do that. And all of that should contribute to this culture of ethics-based, engineering, responsible innovation.

So, what typically happens is, at the end of this, we come up with a set of responsibility objectives. They might go into product requirement documents and shape the way technology’s built. They will shape user experience, research, questions, and surveys, so that they are actually more ethically informed about, you know, the ethical preferences of users. Evaluation criteria of a technology, you know, after it’s launched or before it’s launched, how… what metrics do we use to evaluate a technology? Is it just latency and efficiency, or is it something else? We contribute to clearer communication internally. My favorite ones were when teams asked for ammunition to say no, to not do a certain thing. You know, a vice president might say, like, oh, explore this, and then they deem it as unethical, so we worked with them for a week to figure out what it is, what they need to say, to justifiably refuse to do that. And all of that should contribute to this culture of ethics-based, engineering, responsible innovation.

And, yeah, it was a wonderful time, and I think now it’s time to leave Google and explore other paths.

[Question from the audience]: To mirror Mike’s question about bringing civic engagement into companies, um… You sort of model Google as, like, this idealized city-state. You know, you have 80,000 employees or something, and they’re all learning ethics and thinking about the moral implications of their work, and Mike was talking about how you bring civic… how civic engagement in undergraduate universities might not actually touch the people who are working in the company, but maybe what about: Is there a way to bring civic engagement to people before they reach undergraduate education? There’s only 1% of people in the world to get an undergraduate education.And why has that gone away, say, in this country?

Ben Zevenbergen: Yeah. That’s a very good question. I actually don’t know how to answer… my immediate thing would say that, in popular media, we do engage with these questions. Science fiction movies are typically, you know, philosophy disguised with future technologies. But so yeah, I wonder how you would do that. It’s a good question.

Natalie Roe: We have a lot of questions in the chat.

Ben Zevenbergen: Oh, we do? Oh, sorry.

[Question from the audience, read from the zoom chat]: Is it possible to be successful to change a culture of a workplace? For example, how does one balance building technology with ethical intentions when underlying decision-making is motivated by profit?

Ben Zevenbergen: Could you repeat the last part?

[Question from the audience, read from the zoom chat]: Yes, it says, how does one balance building technology with ethical intentions when underlying decision-making is motivated by profit?

Ben Zevenbergen: Yeah, yeah. Yeah, so the thing we would typically say is that user trust, or social trust in the ecosystem of Google’s technologies, is the most important thing, because that’s where the money is earned in that company when people interact within the ecosystem. So it’s not when you buy a particular phone, or you know, set up a YouTube channel, it’s the engagement that drives the income, typically. So if you lose trust, you will lose that engagement. And the trust of users is, to a very large extent, based on their ethical perceptions of this actor. Now, of course, you know, these are huge companies, and there aren’t many alternatives, so that makes it a little bit more difficult to, that that argument fully holds, but I think it’s the sort of the public responsibility that these companies have, and if they lose that legitimacy, they will also lose their income. And I think a similar thing can be said for science, is that, you know, you’re publicly funded, it takes a set of scandals to lose that trust in science. We’re already seeing some loss in – I guess that’s not self-inflicted – but there can, I mean, throughout the decades, there have been many scandals in science, where the response was sort of top-down research ethics laws. But I think to, you know, to combat, like, those are very reactive, typically, and to make sure we don’t have those types of scandals, these approaches could contribute to helping.

Ben Zevenbergen: I’m sorry. No, we’re done. This was my last image. Thank you.

Natalie Roe: Alright, well let’s thank Ben!

[Applause]

Ben Zevenbergen: Thank you.